The English language had been brought to Britain by

the Germanic tribes—Angles, Saxons and Jutes. They

gave us their words for concrete things like sun, moon,

hand, foot, heat and cold.

When St. Augustine brought Christianity to the land in

597 A.D., Latin and Greek words were added.

Ecclesiastic words gave the words for abstractions and

foreign concepts like angel, disciple, psalm, lion, cedar,

orange and oyster.

The Viking raids of 750-105 brought Danish and

Norwegian words. When King Alfred overcame the

Vikings, he had English rather than Latin used in the

schools and instituted a record of current events, The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicles.

All these sources added variety and synonyms to the

language.

The Norman Invasion of 1066 brought French to

England. William the Conqueror was crowned in

Westminster Abbey, and French became the language

of society and culture; Latin, of religion and learning;

and English of common speech.

The English-speaking peasants in the fields thought in

terms of cows, sheep and pigs, while their French

overlords saw them as the beef, mutton and pork on

their tables. English not only survived, it was enriched

by each of these waves.

In 1325, the chronicler William of Nassyngton wrote:

Latin can no one speak, I trow,

But those who it from school do know;

And some know French, but no Latin

Who’re used to Court and dwell therein,

* * * * *

the Germanic tribes—Angles, Saxons and Jutes. They

gave us their words for concrete things like sun, moon,

hand, foot, heat and cold.

When St. Augustine brought Christianity to the land in

597 A.D., Latin and Greek words were added.

Ecclesiastic words gave the words for abstractions and

foreign concepts like angel, disciple, psalm, lion, cedar,

orange and oyster.

The Viking raids of 750-105 brought Danish and

Norwegian words. When King Alfred overcame the

Vikings, he had English rather than Latin used in the

schools and instituted a record of current events, The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicles.

All these sources added variety and synonyms to the

language.

The Norman Invasion of 1066 brought French to

England. William the Conqueror was crowned in

Westminster Abbey, and French became the language

of society and culture; Latin, of religion and learning;

and English of common speech.

The English-speaking peasants in the fields thought in

terms of cows, sheep and pigs, while their French

overlords saw them as the beef, mutton and pork on

their tables. English not only survived, it was enriched

by each of these waves.

In 1325, the chronicler William of Nassyngton wrote:

Latin can no one speak, I trow,

But those who it from school do know;

And some know French, but no Latin

Who’re used to Court and dwell therein,

* * * * *

But simple or learned, old or young,

All understand the English tongue.

The period we call Middle English, from 1150-1500, marked

the domination of London English and of the written

language. Geoffrey Chaucer's CanterburyTales marked the

rebirth of English as a national language.

His printer, William Caxton, and Henry V, the first king to use

English in official documents, helped strengthen the

language and prepare it for perhaps its greatest writer,

William Shakespeare, who wrote in the vernacular and

showed how expressive it could be.

It’s impossible to overestimate Shakespeare's importance to

the history of the English language. His vocabulary was

twice that of the average educated person today.

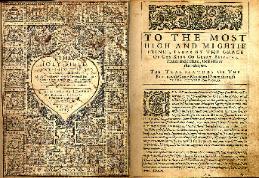

By 1600, nearly half the population was literate. Outside of

the universities, people preferred to read English rather than

Latin or Greek. King James I had his influential Bible, the

King James Version, translated into English.

Last Saturday, March 28, Frank, Kathy, Katyana and I went to

the Huntington in San Marino, where we saw several of these

classics of the English language.

The Huntington is a library, art collection and gardens on the

estate of Henry E. Huntington, railroad, utilities and real

estate magnate, who willed the core of his outstanding

collections of books, art and plants to a nonprofit educational

trust hosting over 500,000 visitors a year.

Other articles in this website include Standardization and

Spread, 3 Influential Writings and My English.

I'd love to hear your reactions to this and any other websites,

as well as your suggestions for future themes. Just write me

at b.silvey@sbcglobal.net.

All understand the English tongue.

The period we call Middle English, from 1150-1500, marked

the domination of London English and of the written

language. Geoffrey Chaucer's CanterburyTales marked the

rebirth of English as a national language.

His printer, William Caxton, and Henry V, the first king to use

English in official documents, helped strengthen the

language and prepare it for perhaps its greatest writer,

William Shakespeare, who wrote in the vernacular and

showed how expressive it could be.

It’s impossible to overestimate Shakespeare's importance to

the history of the English language. His vocabulary was

twice that of the average educated person today.

By 1600, nearly half the population was literate. Outside of

the universities, people preferred to read English rather than

Latin or Greek. King James I had his influential Bible, the

King James Version, translated into English.

Last Saturday, March 28, Frank, Kathy, Katyana and I went to

the Huntington in San Marino, where we saw several of these

classics of the English language.

The Huntington is a library, art collection and gardens on the

estate of Henry E. Huntington, railroad, utilities and real

estate magnate, who willed the core of his outstanding

collections of books, art and plants to a nonprofit educational

trust hosting over 500,000 visitors a year.

Other articles in this website include Standardization and

Spread, 3 Influential Writings and My English.

I'd love to hear your reactions to this and any other websites,

as well as your suggestions for future themes. Just write me

at b.silvey@sbcglobal.net.

| April 2015 |

| Billie Silvey |

An eclectic website about Women, Christianity, History, Culture and

the Arts--and anything else that comes to mind.

the Arts--and anything else that comes to mind.

The History of the

English Language

English Language

| Katyana in the Rose Garden at the Huntington |